Untangling health care costs, one cord at a time

Nurses have assigned an array of nicknames to the web of medical lines, cords and tubes stationed by a patient’s bedside. Snake pit. Spaghetti. Rat’s nest. With no universal system to sort the numerous cords and tubes, they frequently get twisted and disorganized. For health care workers, the problem of discombobulated cords can range in severity from a time-consuming nuisance to an occasional tripping hazard to something far more dangerous.

Lindsey Roddy, a Ph.D. student studying nursing science at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, is seeking to untangle the web. Having worked in intensive care for four years, Roddy has seen these issues play out.

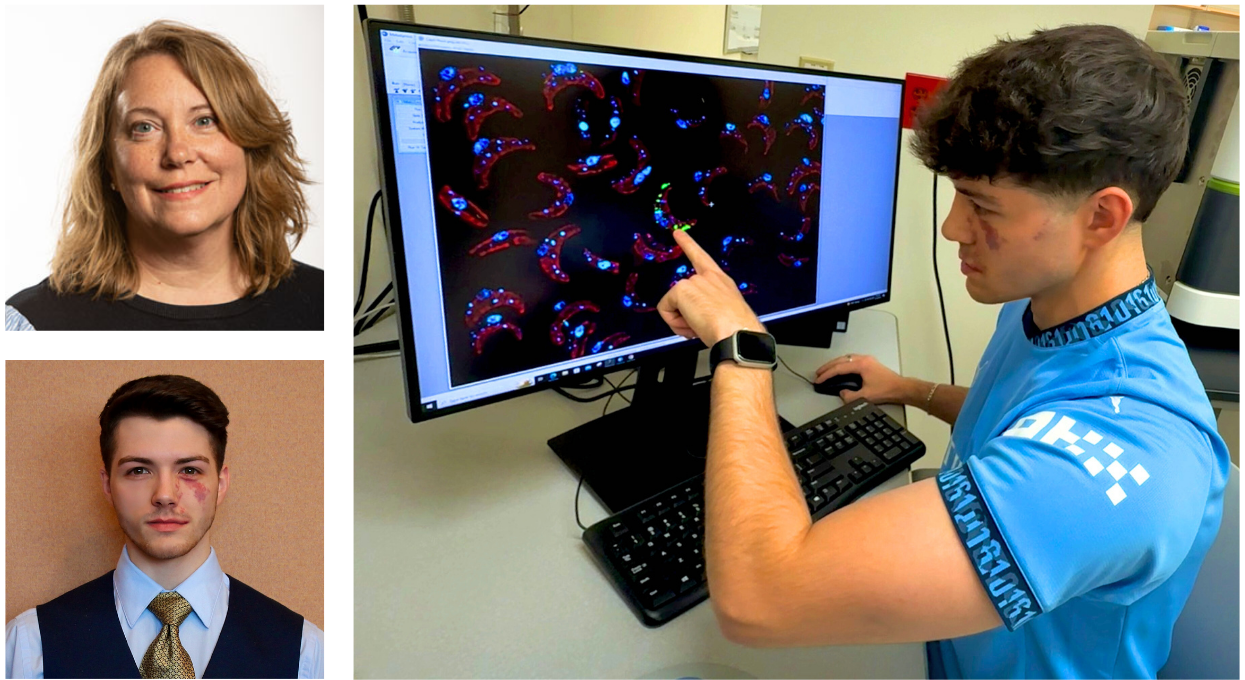

UW-Milwaukee Ph.D. student Lindsey Roddy is developing a new product to organize the web of medical lines, cords and tubes by the bedsides of hospital patients. Nurses often turn to makeshift solutions, like using tongue depressors and medicine cups taped to the bed.

“I was being trained on a cardiac bypass patient who had just had open heart surgery,” Roddy said, recalling one particularly dicey situation. “Everything started to crash and we couldn’t figure out what was going on. We were watching their blood pressure drop and we were ready to call a code, bringing everyone in and doing compressions, when we realized there was blood going into the bed. We realized ‘OK, it’s the lines’ … Something was unscrewed and the life support medication was running into the bed. Thankfully, we found that before something happened.”

If she had witnessed that, Roddy figured, surely other health care professionals have, too. The opportunity to develop a solution came at UWM, where Roddy happened to be placed with professors who are pursuing their own innovation projects in the health care sector. Roddy was asked whether she had any ideas to contribute. Her idea was born – a loop that attaches to a bedrail or solid surface, designed to organize up to 15 lines and allow patients to move freely. Roddy submitted her idea to the university’s research foundation. Soon, she also became involved with the UWM Student Startup Challenge, a branch of the National Science Foundation’s Innovation Corps program. A provisional patent was filed in January and a group of UWM engineering students are developing a prototype. The prototyping process is being helped by a recent $2,400 grant from I-Corps.

When it comes to competition, Roddy said there is only one other product that’s made it to the bedside, and it isn’t particularly mobile. As she moves toward the goal of ultimately getting her product into hospitals, Roddy is still considering how the product will be produced and at what price point. She said the process would be helped by having a manufacturing and distribution partner that’s already established in the health care sector.

“So far we’re on the right track,” Roddy said. “This is always a risky business, bringing something to fruition. I’m just seeking the advice of my business advisors … finding information from the right people and trying to build this case. We’re not quite at a point where we would be pitching to investors to get investments, but we’re working with the research foundation on licensing as we speak.”

As part of her research, Roddy interviewed 40 health care professionals to determine whether the problem is widespread. It is. Asked about the cord problem, a majority of frontline health care staff said they trip over lines on a daily basis. Of 30 frontline staff, 80 percent said they had experienced “close calls or safety events,” meaning a line pulled out or they tripped on a line, and 30 percent of those said they had witnessed a life-threatening safety event. The surveyed health care professionals also said they spend an average of 30 minutes per shift organizing lines. Currently, Roddy said, most nurses create makeshift solutions to keep the cords sorted. They turn to tongue depressors and medicine cups taped to the bed, or stickers as labels – jerry-rigged solutions that frequently break and don’t allow for much patient mobility.

“We work with what we have and we make things,” Roddy said. Roddy envisions how her simple device could achieve cost reductions. What if that half hour nurses ordinarily spend organizing cords could be used for something more productive? “We spend the most on health care and of all the first-world nations, we have the poorest safety, the poorest quality and value,” Roddy said. “So, how can we fix this? What can we do to make this better? You have to be innovative.”

Featured in BizTimes here.